The traditional tissue biopsy method of cancer diagnosis has been around for more than 50 years. The method finds the presence of cancer, but frequently too late to treat it successfully.

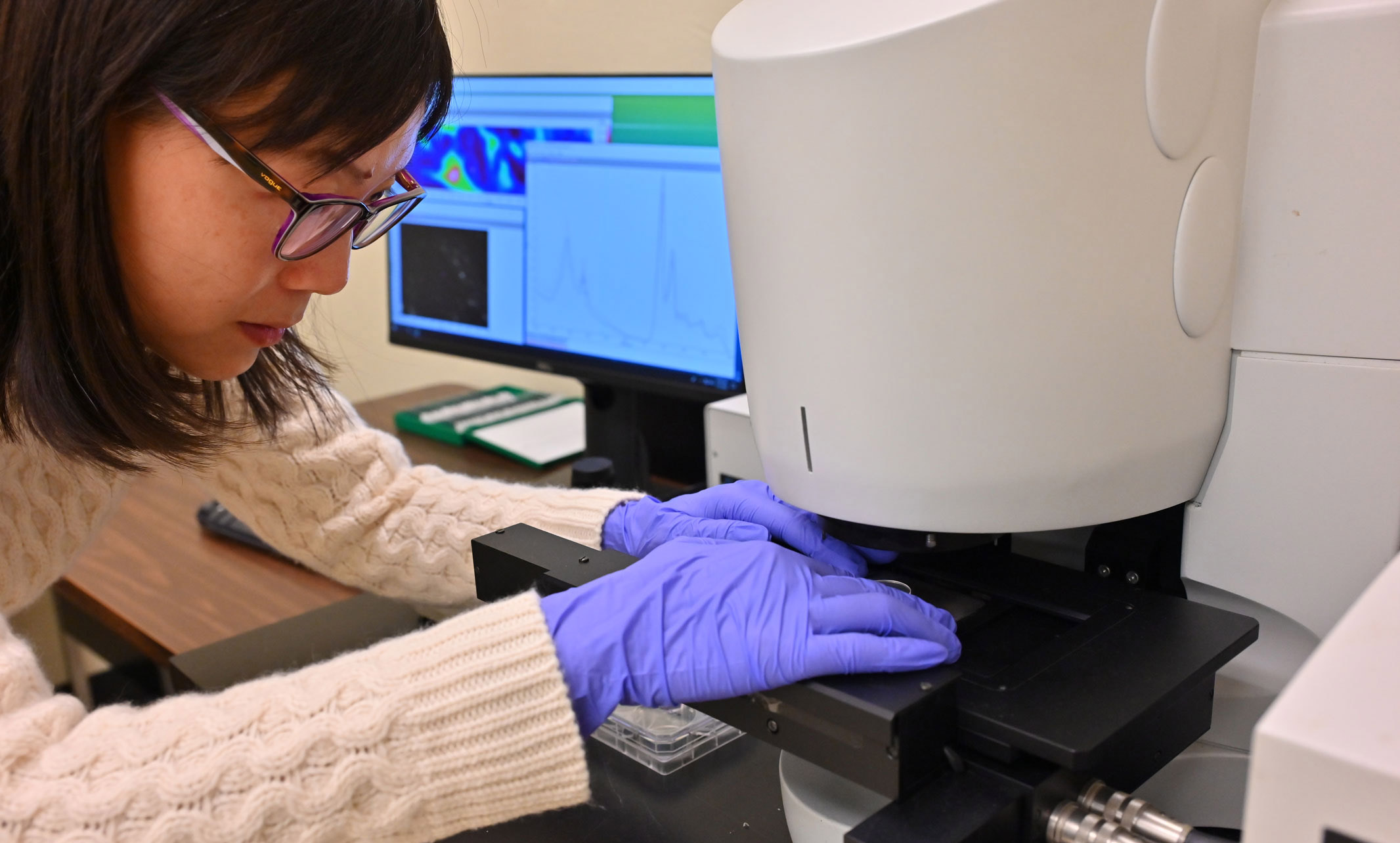

As a researcher at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Dentistry, Rose Wang, Ph.D., focuses on establishing a system to identify the risk of cancer through artificial intelligence and infrared technology. She is confident that this method, designed to intercept precancerous lesions before they become a deadly form the disease, can be applicable to other forms of cancer as well.

The scientific community has taken note of the promise behind Wang’s research. She received a $430,000 developmental research grant in January for her innovative research from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

“We’re not trying to diagnose cancer itself,” Wang said “We are creating a system to detect high-risk precancers and to prevent them from becoming cancer. If we’re able to detect it early on, there’s more we can do about it, and the treatment is more effective. I’m very excited about that.”

Wang is studying the application of artificial intelligence, such as machine learning, to analyze the biochemical data from tissue samples using infrared spectroscopic imaging, a device that provides higher dimensional data than traditional imaging methods, such as a microscope. She uses both specialized software and open-source computer programs to train machine learning models to extract the most important information from what the spectroscopy shows. The level of detail is immense, with each pixel providing thousands of variables across different wavelengths.

“Manually reviewing the data is almost impossible,” Wang said. “that’s why we need to use machine learning to extract the important information and to train models for automatic risk stratification.”

Wang has pulled together an impressive research team from not only the UMKC School of Dentistry, but also the UMKC School of Science and Engineering as well as the University of Kansas Medical Center. Her multidisciplinary team covers a wide range of expertise: infrared spectroscopy and imaging, clinical pathology, artificial intelligence, oral biology and cancer biophysics.

The current gold standard for cancer detection is the histopathological diagnostic approach, cutting tissue sample for a biopsy. The sample is then sent to a pathologist to be visually evaluated for the presence of cancer. "Pathologists spend years to train their eyes to see those morphological anomalies and say cancer or no cancer,” Wang said.

The pathologist looks for what is called morphological changes of cells and tissues. Unfortunately, these changes don’t show up until the cancer is already progressing. According to Wang, the problem is that 70% of all oral cancers are diagnosed at late stages, leading to a low 50% survival rate at the five-year mark.

Precancerous lesions are not cancer but have increased risk of becoming cancer. According to Wang, pathologists don't yet know how to differentiate which precancerous lesions, known as dysplasia, will transform into cancer. Sometimes the cells just stay in the precancerous state without becoming cancer. If the pathologist finds mild or moderate abnormalities, frequently clinicians will opt to observe the problem area over time.

"But what if the patient did come back in a year and suddenly they have cancer from even mild dysplasia?" Wang said. "Right now, there is no reliable way to determine which precancerous lesions will become cancerous."

The other issue is the subjectivity of the traditional process. Wang said two well-trained pathologists can provide different diagnoses for the same tissue biopsy.

“The system we are developing will provide objective and quantitative diagnostic information and facilitate clinicians to make better management plans for their patients,” Wang said. “Oral cancer survival is highly stage-dependent, and early detection can significantly improve patient survival rate. If we can catch them early, we can save lives.”