The death of George Floyd at the hands of Minnesota police in May 2020 set off international protests and focused a spotlight on the Black Lives Matter movement. But for Black people and people of color, it was another reminder of the urgency and foundational change needed to reach racial equality in the United States — an issue so many UMKC alumni are working to address in their careers, communities, homes and day-to-day lives.

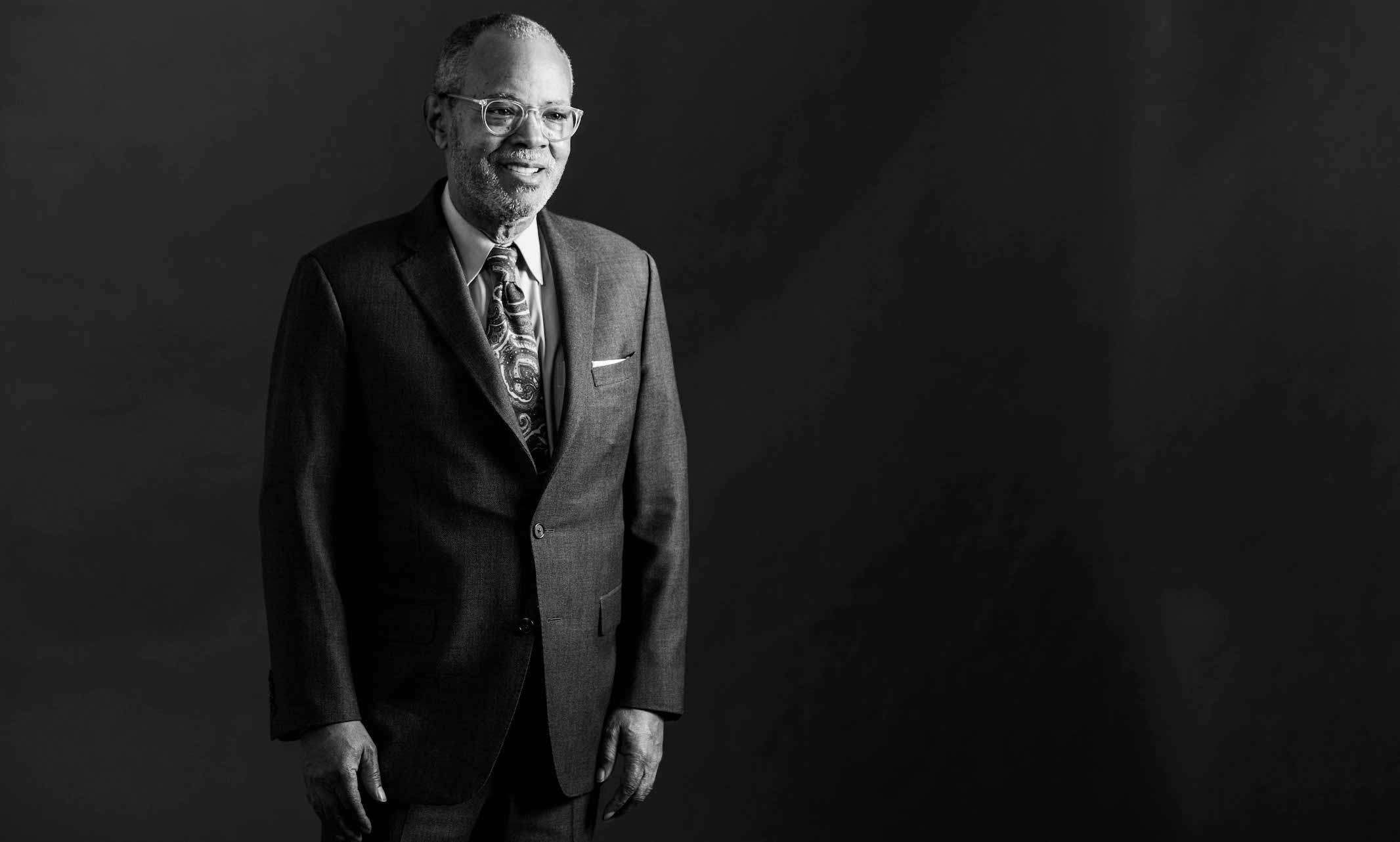

We spoke with School of Law alumnus Mark S. Bryant (J.D. ’74), who grew up during the civil rights movement and has spent much of his adult life fighting racism in government, nonprofit work and the private sector. His story sounded very much like the kind of work and activism our alumni and students are doing now — 50 years later.

Using Bryant’s experience as a guide, we’ve examined the parallels between then and now and how our UMKC family is making a difference in the lives of people of color.

Then and now

“The civil rights movement was led by religious and civic leaders and fueled with the energy of young people. The Black Lives Matter movement is led by young people.”

Bryant was born into a segregated Kansas City and as a child was inspired by his parents. His mother was one of the first Black students admitted to the University of Kansas City (now UMKC) School of Education. His father was a dining car waiter on the Kansas City Southern Belle, “one of the best jobs a Black man could have," Bryant recalls.

When racial segregation was eased in 1959, Bryant's family was one of the first Black families to move south of 27th Street. At first, Bryant was surrounded by white people in his new school and neighborhood, but soon those teachers and students moved — his introduction to “white flight."

He remembers his father discussing politics at the kitchen table and being an early organizer of Freedom, Incorporated, a Kansas City organization that empowers African Americans in the political process. At the time, there were no Black people elected to public office. When Bryant’s father retired, he ran three times against the incumbent state representative for their district. His father never won, and a young Bryant witnessed the pain that it caused. Bryant resolved to get his law degree, enter politics and make his parents proud.

Today, Mahreen Ansari (’22) and Daniel Garcia-Roman (’21) are two UMKC students fighting for equal treatment of all individuals — continuing the work Bryant’s father began so many decades ago.

Ansari, a political science and international studies major with a pre-law emphasis, serves as president of the Student Government Association and communications director for the College Democrats of Missouri. She’s also a writer for the UMKC chapter of Her Campus, an online magazine for women in college, and a community organizer with the Sunrise Movement of Kansas City, a climate justice organization.

For Ansari, her interest in social justice was really sparked when she left high school, where she’d been surrounded by other BIPOC (Black, indigenous and people of color).

“I was lucky enough to have been somewhat sheltered by going to high school in a district mostly filled with other BIPOC,” she says. “But coming to a [predominantly white institution] I had to come face to face with a lot of things.”

Even in her earliest activism, Ansari saw a long road ahead to achieve lasting change in the realm of racial and social justice.

“It’s going to take a very conscious effort to undo those systems — possibly completely dismantling them — to stop and prevent further harm,” she says.

Garcia-Roman is a studio art major with plans to earn a master's degree for art education and teach in the Kansas City, Missouri, School District. He is also an artist and volunteers with the Kansas/Missouri Dream Alliance, an organization that serves undocumented youth and encourages cultural exploration through visual arts at the Mattie Rhodes Center.

Garcia-Roman says his interest in activism started close to home.

“My older brother is a DACA [Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals] recipient, and once he graduated from high school, I realized there are intentional policies in place that hinder his mobility in life,” Garcia-Roman says. “I reflected and found the forces that affected me and the people closest to me were social forces like misogyny, homophobia, xenophobia and

racism. And that a small group of people can cause change through activism.”

Making a difference

“You could name and count them by hand … there were so few Black attorneys that I was a novelty.”

Just as he planned, Bryant became a lawyer and entered public service. After graduating from the UMKC School of Law in 1975, Bryant took a job as assistant public defender.

At the time, he says, he was one of very few Black lawyers in Kansas City. That unique role allowed him to participate in organizations like the Council on Education, Citizens Association, Committee for County Progress and Freedom, Incorporated, but it didn’t keep him from experiencing discrimination.

“Discrimination was most pronounced during encounters with law enforcement," he says. "It didn’t matter if I was driving, flying or boating. I had more encounters with law enforcement than my counterparts, and it was unpleasant."

Bryant served as a Kansas City, Missouri, City Council member from 1983 to 1991 and notably helped resolve decade-long litigation around the Bruce R. Watkins Roadway that had left Kansas City’s 5th district devasted by blight.

Today, Bryant is a land use and public law attorney at Rouse Frets White Goss Gentile Rhodes, P.C. He has also worked with Community Builders of Kansas City, a nonprofit that redevelops areas that lack essential services. With Bryant's help, the organization developed an ambulatory health-care facility, multi-family housing, office buildings and a retail shopping center in the vicinity of Blue Parkway and Cleveland Avenue, projects that, according to Bryant, “had a catalytic affect and transformed an area of Kansas City that was sorely in need of redevelopment.”

Like Bryant, alumna Sandra Thornhill (B.A. ’13, M.P.A. ’17) has served her community in a myriad of ways since graduating from UMKC with both an undergraduate degree in sociology and a Master of Public Administration. She says her young son, Jerren, has been a major source of motivation for her advocacy and racial justice work.

Thornhill collaborates with Shirley’s Kitchen Cabinet, a Black women-led, nonpartisan, nonprofit organization dedicated to amplifying the voices of Black women. She also serves as a community liaison for birth justice advocacy with Uzazi Village, established to decrease maternal and infant health disparities found in the urban core, particularly among African-American women.

Recently, Thornhill worked to get the CROWN (Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair) Act passed in Kansas City, Missouri. Under the CROWN Act, Kansas City employers cannot implement appearance policies that prevent employees from wearing hairstyles or textures traditionally associated with race. This protects employees from being discriminated against for wearing their hair naturally or in styles such as twists or locs. Kansas City was only the second city in the nation to adopt the policy.

“The CROWN Act makes a huge difference for a couple of reasons: for pride as a Black person and as a measure of protection for the Black community," Thornhill says. "For a city to recognize its racist past and act to protect its most historically marginalized community — the Black community — this begins to allow one to shake the burden of internalized inferiority in exchange for pride in one's full essence of Blackness."

Since childhood, Thornhill has been keenly aware of societal white-washed standards of beauty, often rebelling against them through eccentric expressions of hair and style. Still, Thornhill wondered how her hair would dictate how people treated her at the office. For professional settings, she would sometimes style her hair to mimic white beauty standards.

“The dichotomy I faced was to either embrace my ancestral intuition of beauty, passed down by generations of Black women around me, or to subscribe to society's propaganda in order to climb the corporate ladder," she says.

Latrina Collins (B.S. ’93), a UMKC accounting graduate and former director of planning, program development and evaluation at the Full Employment Council, encourages employers to invest in diversity on an internal level, as well

“It is imperative that each company have staff dedicated to diversity, equity and inclusion,” she says. “It is not enough just to hire people of color, but companies must contribute to helping them succeed in terms of leadership development and working with each employee on a plan

for success.”

Looking forward

“The color of my skin has, in many respects, defined my identity. The color of my skin determined where I could live, the schools I could attend, our family income, where I could go and what I could aspire to be. The color of my skin often defines a person’s first impression of me. When you are a person of color, it affects nearly every aspect of your life.”

Even with decades of time between them, Bryant, Ansari, Garcia-Roman, Thornhill and Collins have shared experiences based strictly on the color of their skin. While they are currently enacting change, they agree there is still much work to be done in bridging the equality gap.

“We have to evaluate and change the policies and practices that allow for people to be treated differently in all facets of life — in the workforce, education institutions, criminal justice system, government, health care and so on,” Collins says. “We have to be able to recognize when a system allows for racism, and we have to make those changes immediately.”

Despite the lengths still to go, a vast army of supporters, activists and allies — including many members of the UMKC community — is working to affect real change at every level, from grassroots movements to the highest levels of government.

“I think that through community organizing and legislation we can begin to try and end systemic racism,” Ansari says. “We need organizations that are built around people and their needs that can advocate for and design a better future for everyone.”

As with many movements, change starts on an individual level. Collins believes people should start their own journey with a bit of empathy.

“We have to recognize our own unconscious bias," she says. "You might not experience racism yourself, but step into the shoes of those who have experienced it and understand that it does exist."