Imagine a doctor sitting down with you and telling you that you have cancer. Because that information makes you feel bad, is it an attack? Or is it the first step in a journey toward healing?

Now, replace the word “cancer” with “racist,” and try to think about it the same way. That was the complex and nuanced message shared by author Ibram X. Kendi in the 2021 Martin Luther King Lecture, sponsored by the Division of Diversity and Inclusion at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

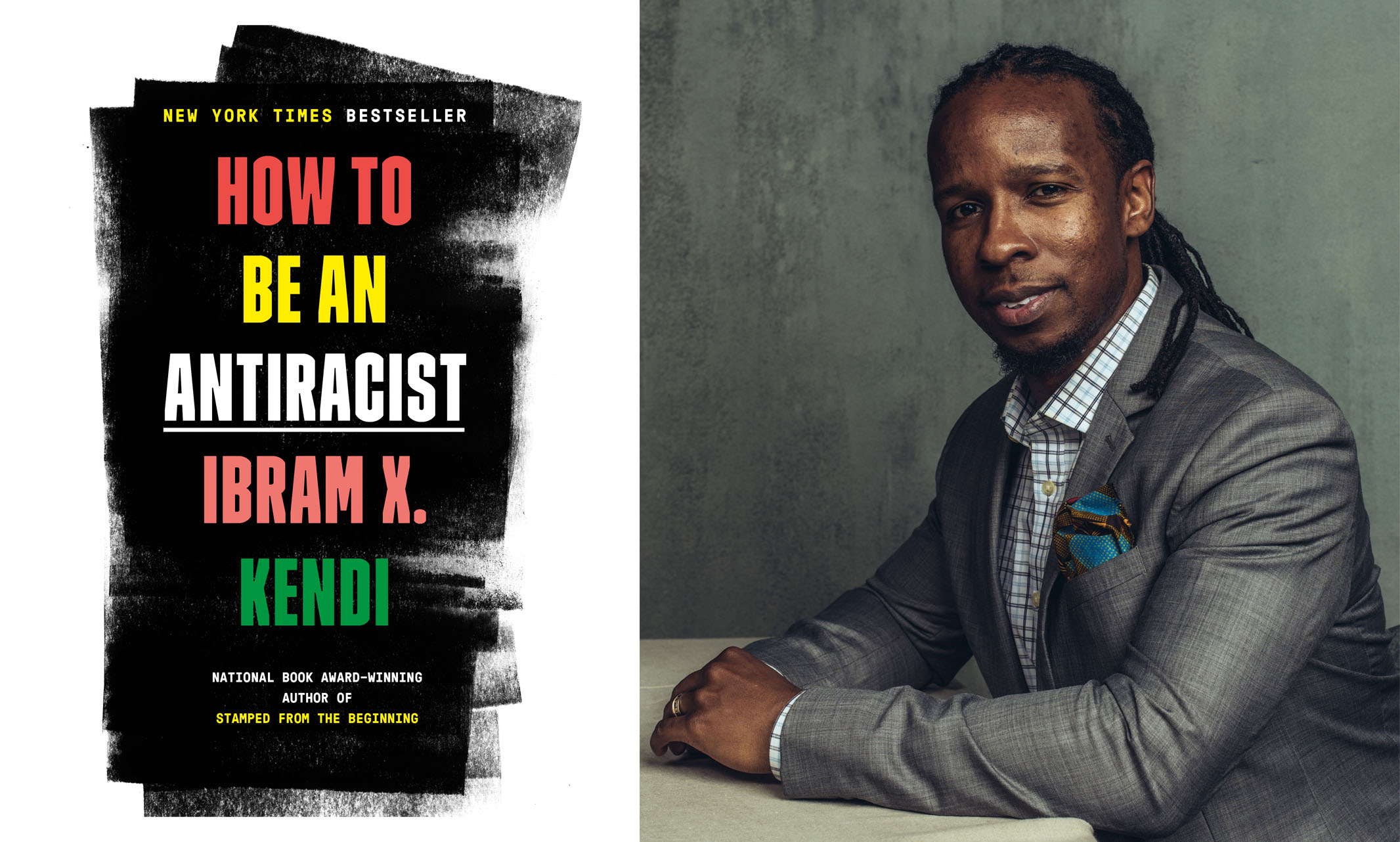

Kendi, the author of numerous books including “How to Be an Antiracist,” said that “racist” and “antiracist” are not fixed categories; people move in and out of the categories based on their thoughts and actions. “To be antiracist is to actually admit to times when you are being racist,” Kendi said.

When people are confronted with knowledge that their statements or actions are racist, he said, they should view that message as a diagnosis, not an attack – a message from someone who wants them to get treatment and help.

“They should realize that to be antiracist is to accept that diagnosis, to accept that when you supported a policy that specifically repressed Black wealth, that is a racist policy,” he said.

The 2021 lecture was delivered in a question-and-answer format, in a dialogue between Kendi and Mikah Thompson, J.D., associate professor in the UMKC School of Law. The wide-ranging discussion covered topics ranging from antiracism to the coronavirus pandemic and the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol.

Kendi also said it is important to differentiate between the terms “racist” and “racism.” While individual thoughts, statements and actions can be racist, “racism is fundamentally institutional, fundamentally systemic, fundamentally structural. Individuals do not practice racism. Institutions do.”

Whether an individual is behaving in a racist manner is a question of whether those actions are upholding the structure of racism, Kendi said. “As individuals, we are either upholding, or challenging, the system of white supremacy and racism. Are we as individuals resisting this system, or are we upholding it?”

An example of racist thinking that went largely unnoticed, Kendi said, was the reaction by many to statistics showing that infections and deaths from the coronavirus were significantly higher among people of color.

“The immediate response was, ‘what are those people doing wrong?’ The antiracial response is, ‘what policies and practices, historic and current, are leading to those disparities?’ Blacks are dying at higher rates, not because of having more preexisting conditions or not taking the pandemic seriously enough. It was less access to health insurance; it was that Blacks are more likely to be working in situations where they are not able to work from home,” he said. “Even middle-income Black folks are more likely to live in neighborhoods with higher levels of air and water pollution.”

Kendi said denial of racism was widespread as people reacted to the Jan. 6 insurrection.

“Americans say, ‘This is not who we are. There are not attempted coups in the United States of America.’ People who say that have not read American history, in which there was coup attempt after coup attempt after coup attempt during Reconstruction. They deny this country was founded on both racism and freedom. They want to say it was just founded on freedom.”

Americans need to recognize the racist roots that drove the insurrection, Kendi said.

“If you do not acknowledge that white supremacists are the greatest domestic terrorist threat of our time, will elected officials have the will and the resources to respond to the threat?” he asked. “People can’t accept that the most dangerous faces in America are white.”

Kendi is the Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities at Boston University and the founding director of the B.U. Center for Antiracist Research. He is the author of many books including “Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America,” which won the National Book Award for Nonfiction, making him the youngest-ever winner of that award. In 2020, Time magazine named Kendi one of the 100 most influential people in the world.

Beginning with the Rosa Parks Lecture on Social Justice and Activism in 2007 and annually since 2009 with the Martin Luther King Lecture Series, the Division of Diversity and Inclusion honors these individuals’ tremendous contributions to furthering civil rights by bringing national thought leaders to campus, who provide insight and advocacy to current civil rights issues of education, economic and justice system inequalities.