What could cause a nurse to leave family and safety behind to work at a New York City hospital filled with COVID-19 patients, many of them destined to die on her watch?

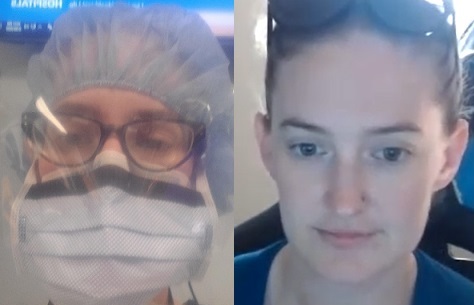

“I really wanted to help my fellow nurses,” said Hanna Bates-Crosby, RN, who works at the UMKC School of Dentistry and is trained as an emergency room nurse. “I went with my sister, who’s also a nurse, because we knew the nurses and doctors in New York were struggling, drowning in patients. I didn’t know how I could ethically not go and use my skills to help them.”

Bates-Crosby and her sister, who is trained in intensive care, were among the first of thousands of nurses from across the country who went to New York to help. They arrived March 26, just after a week in which the number of COVID-19 patients in New York City had increased tenfold.

“It truly was a war zone,” said Bates-Crosby, who worked the 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. shift for seven straight days at one of the hardest-hit hospitals in Queens. “A trauma bay designed for four patients would have eight or 10 patients in it, and one nurse, because that was all we had. Another room meant for a few heart attack patients would have a dozen COVID patients and two nurses.”

On one of her shifts, 30 people died. “Those people who don’t believe they were loading bodies into semi-trailers need to believe it,” she said. “It happened.”

Away from the emergency room, on the regular hospital floors, “it was still practically all COVID patients, and if someone came in with something else, within a couple of days they could have COVID. There was no way to separate and protect the non-COVID patients,” she said.

“But we went in knowing it wasn’t going to be normal nursing. We were going to see a lot of death, and not be able to do much for many of the patients. It was hard, being there for a patient and sedating them and putting them on a ventilator, knowing the odds of them coming off were not good.”

She remembered one patient in particular. Making a rectangle around her eyes with her hands, to represent her hospital mask and other protective gear, Bates-Crosby said, “Knowing my face, this much of my face, was probably going to be the last face he saw — that was hard.”

“It was hard, being there for a patient and sedating them and putting them on a ventilator, knowing the odds of them coming off were not good.”

But the difficult experiences were worth it, she said, to do what she could to support her colleagues. “One doctor asked me where I was from, because I sounded different,” she said. “She couldn’t believe I had come all the way from Kansas City to help them.”

Since returning, she said, “I have dreams sometimes where I’m in that emergency room. And I’m a very auditory person, so for a while I would wake up and hear ventilator alarms going off. But I was only there a week, so I’m doing all right. I worry about the nurses who are still there, getting COVID or just being exhausted.”

When she and her sister returned to Kansas City, they still had to quarantine in a motel for two weeks. “That was hard, too. My husband was really good about it, bringing food and clothes, but he said, ‘It’s like you’re back, but you’re not really back.’ ”

When quarantine was over, she finished coursework that added a bachelor’s in nursing degree to her RN, and in August she will start classes toward becoming a nurse practitioner. Bates-Crosby also picks up shifts administering infusion therapy in people’s homes. But she’s most looking forward to working again at the School of Dentistry as its clinics reopen, she hopes in July.

“I really miss the students,” Bates-Crosby said. “It will be good to be back.”