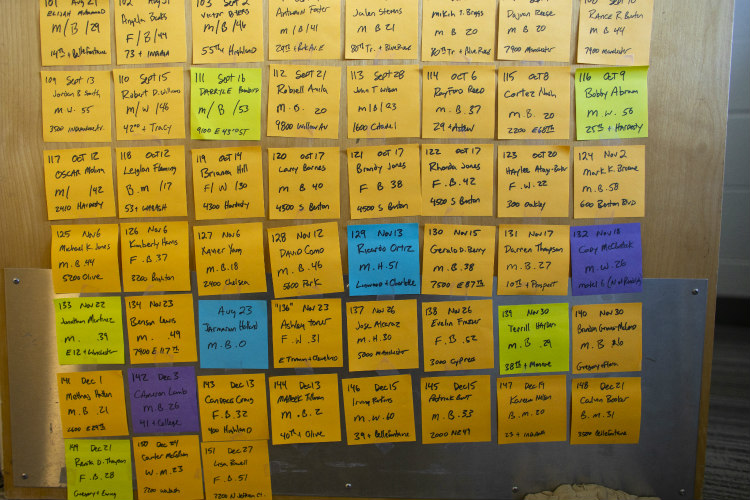

In January 2019, criminology and criminal justice professor Ken Novak noticed an unusual pattern of homicide cases in Kansas City and casually decided to track them using color-coded sticky notes and posting them on his office door. He intended to spark a conversation.

On each note he recorded the date, victim name, victim demographic and the location. Orange for gun violence, blue for other, yellow for unknown and purple for officer-involved. He wanted students and colleagues to stop and ask questions, to take in what was happening and be led to help find a solution. He detailed his findings on Twitter at the start of 2020.

What stuck out to you the most about the homicide rate last year?

The thing that stuck out to me in general was the number of gun-related homicides – it’s clear that guns are involved in nine out of every 10 homicides.

“I hope this humanizes crime statistics. Behind every homicide is a victim and grieving families experiencing unimaginable trauma.”

151 homicides in one year? That’s a lot. Is that the highest it’s ever been?

There were several years in the 1990s when the raw number of homicides was higher. In fact, there were more homicides in 2017 than in 2019. But I believe it’s better to examine the population-adjusted homicide rates and compare Kansas City’s rates to national trends.

In the 1990s, the national homicide rate was almost twice as high as it is today. Since then, the national rate trended downward, where Kansas City’s homicide rate is stable. In 2019, Kansas City’s homicide rate was roughly six times higher than the national rate, and this disparity between Kansas City and the U.S. is the highest it has ever been.

What can we attribute to the heightened rate of gun violence in our city?

Several different factors contribute to the heightened rate of gun violence in Kansas City.

First: Research demonstrates that cities and counties in states with lenient gun laws have more gun homicides, even after considering other factors.

Second: There is a culture of gun violence in Kansas City, as well as in other urban areas in Missouri, perhaps due to the availability of guns. Using guns to settle disputes and arguments is normative in Kansas City, so we run the risk of viewing this violence as normal because it is what we have become accustomed to expect. Additionally, many homicides are a result of retaliatory violence. “Settling the score” with guns rather than the criminal justice system has become normalized behavior.

Third: Many affected by gun violence do not view the criminal justice system as effective, fair, impartial or transparent. Only about half of homicides are cleared by the police, and only about 20% of non-fatal shootings result in an arrest. When witnesses and victims don’t see people being held accountable for their actions, they are less likely to cooperate with detectives and prosecutors. Add in the fact that witnesses and victims may also fear retaliation if they cooperate, their motivation to collaborate with the police goes down even further. It’s a vicious cycle.

“There is no single solution to this problem, and there is no single strategy we can implement...”

Your goal when you started posting these notes on your door was to start a conversation and you’ve done just that, especially with the recent wave of media coverage after your Twitter thread. What do you hope the community will take away from your findings?

I hope this humanizes crime statistics. Behind every homicide is a victim and grieving families experiencing unimaginable trauma. It’s easy to lose sight of this fact. I also wanted to draw attention to how homicide victimization clusters by demographics. Young black males experience a disproportionate amount of victimization – about 95 times higher than the general U.S. population. The burden and trauma of homicide is not shared equally across everyone in KC.

You were previously on the board for KC NOVA (the Kansas City No Violence Alliance). What community initiatives are you currently involved in to help solve criminal justice issues in Kansas City?

I am currently working with the Kansas City Police Department on a hot-spot policing initiative in the most violent areas in eastern Kansas City — where many of these shooting occur. I am also working with the police and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms on an initiative to link shootings by examining ballistic evidence left behind at crime scenes. Both of these are sponsored by the U.S. Department of Justice.

“In 2019, Kansas City’s homicide rate was roughly six times higher than the national rate, and this disparity between Kansas City and the U.S. is the highest it has ever been.”

Interesting! We’re looking forward to hearing more about those initiatives as they progress. What about those of us in the community? What can we do to help solve the gun violence issue?

There is no single solution to this problem, and there is no single strategy we can implement. Kansas City needs a violence-reduction portfolio of strategies. We have learned some crime prevention strategies work better than others do and, over time, science has developed evidence-based solutions to reduce crime. Citizens should demand evidence-strategies be given priority within this portfolio.

You mentioned that you started this as a casual effort. Are you planning to do it all again this year?

I don’t think I’m going to do this in 2020. I never intended this to be an annual exercise.