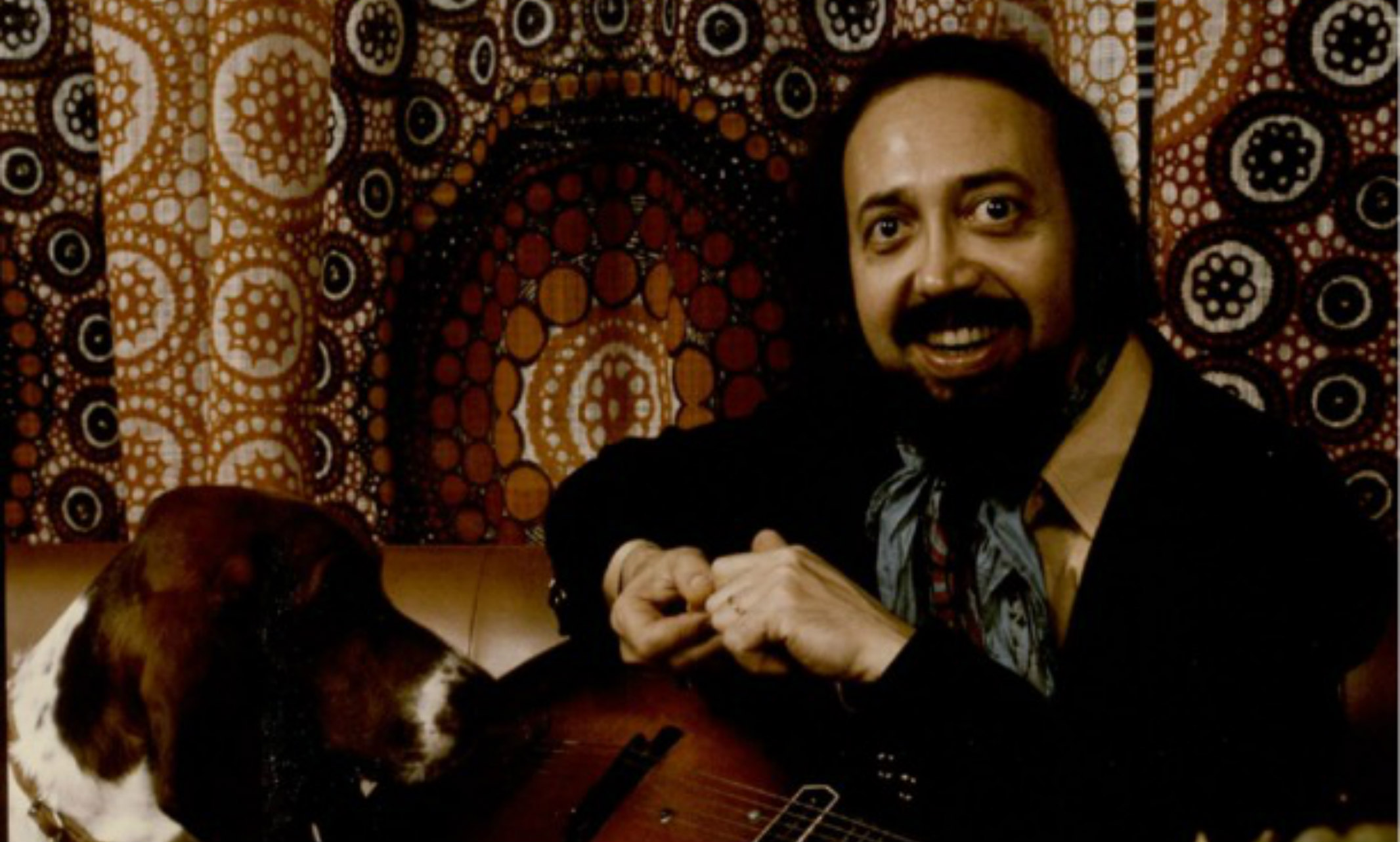

Barney Kessel began playing guitar when he was 12 years old in his hometown of Muskogee, Oklahoma. By 1937, at the age of 14, he was playing professionally.

Kessel built a legendary jazz career and an impressive collection of music and manuscripts that archivists and students have worked to preserve in the Marr Sound Archives and the LaBudde Special Collections at UMKC.

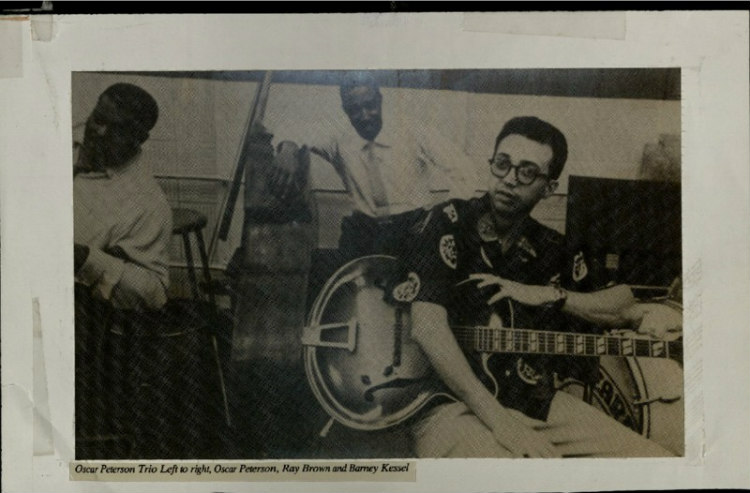

Kessel played with jazz greats, such as Charlie Parker, Lester Young and Charlie Christian. He jammed with Christian for three days and the session had a profound effect on his style. In 1942, Kessel moved to California and played with big bands and studio musicians. He contributed to soundtracks with musicians including Sam Cooke, Elvis Presley and the Beach Boys.

After his death, Kessel’s widow, Phyllis Kessel, made the decision to donate his materials to the Marr Sound Archives and the LaBudde Special Collections.

“Phyllis had been looking for a place to house Barney’s collections,” says Chuck Haddix, curator of Marr Sound Archives. “She contacted Rob Ray at San Diego State. He is the former head of the UMKC collections and recommended she get in touch with us because of our strong holdings in jazz. He knew that we would be able to manage it.”

Phyllis met Kessel in 1987. She was a magazine editor, and while she was on a personal trip, she saw Kessel play with Herb Ellis and Charlie Byrd. She has a natural curiosity about people and an instinct to interview. She was familiar with Kessel and struck up a conversation with him in the park where he was playing.

“Barney was the most talkative of the great guitarists that were there and he loved to talk,” she says.

They married two years later and traveled together often. Phyllis understood the significance of Kessel’s collection and following his death in 2004, she began to think about preserving his legacy.

“I needed to find a home for all that Barney had left behind.”

The donation includes an extensive audio-visual collection and manuscripts spanning the length of Kessel’s career. In addition to the library staff cataloguing and processing the collection, seven students, who referred to themselves as the Barney Bunch, produced a digital exhibit, Barney Kessel; Illuminating a Musical Legacy, of Kessel’s life and work.

“We started the third week of February,” says Lacie Eades, a member of the team from the UMKC Conservatory advanced research and bibliography class led by Sarah Tyrell, Ph.D., associate teaching professor of musicology. “Our goal was to create a virtual exhibit. We worked for about four weeks before the COVID-19 outbreak led to the global shutdown.”

The team moved to working remotely. While it took a few days to adjust, Eades notes that the staff at LaBudde worked to digitize the content the team needed.

“Anything we flagged, anything we needed, the staff retrieved for us,” Eades says. “We met as a group two days a week and there was a lot of group messaging. It was continual cooperation.”

The team knew they needed to determine if they were going to create a biographical sketch or a narrative. The material seemed to lend itself to narrative.

“This class working on a project that shows the artist’s work, gives them the skills to see it through from the research to the digital exhibit – that is the way of the future.”

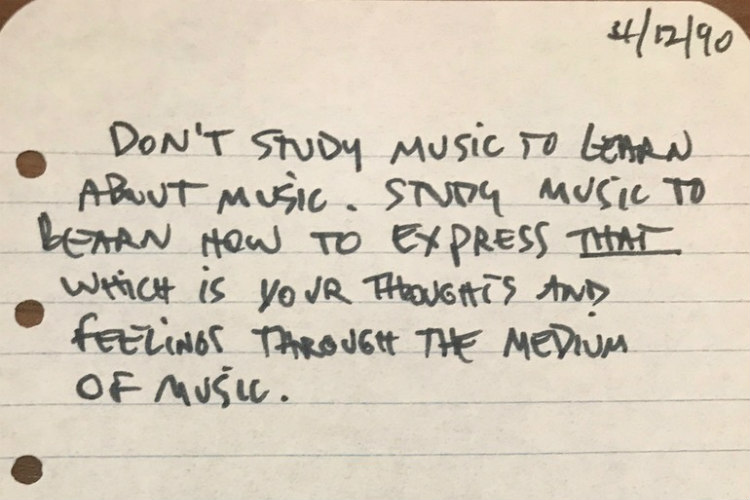

“One of my jobs was to go through his daily planner,” Eades says. “One of the intriguing elements was that on one day he would note, ‘Studio with Elvis.’ And the next day would be, ‘Take boys to the dentist.’ On November 22, 1963 he wrote, ‘President assassinated.’”

Each student took responsibility for different aspects of the research. Bryanna Beasley is pursuing her master’s degree in flute performance and musicology.

“I had the opportunity to work directly with Phyllis,” Beasley says. “Especially during COVID, she became a primary resource. She is funny and intelligent. It was rewarding to work directly with her to create a legacy for scholars and enthusiasts. We are lucky she saved so much of his materials. It enabled us to highlight different aspects of his legacy.”

Phyllis is satisfied and relieved that Kessel’s collection is safe and available for scholars and enthusiasts.

“I have a great interest in keeping Barney’s name and music alive for future generations,” she says. “Sadly, I know how quickly the public forgets our stars. It takes some effort to keep their legacies alive. I truly believe Barney was one of the greatest jazz guitarists that ever lived.”

Sandy Rodriguez, associate dean of special collections and archives, understands that donating a loved one’s material is always very personal.

“They want to give to a place that’s going to be responsible,” Rodriguez says. “As the long-term home for these materials, we work hard to ensure they are cared for over time and are made available for research as soon as possible. Not all collections are processed so quickly. This was prioritized.”

“I have a great interest in keeping Barney’s name and music alive for future generations.”

Haddix appreciates that the team was able to make such a quick pivot to develop the digital exhibit.

“These are brilliant students who treated the project with humor and good will,” Haddix says. “The exhibit tells Barney’s story and is free and open to the public.”

He notes that this turned out to be a great way to manage research.

“This class working on a project that shows the artist’s work, gives them the skills to see it through from the research to the digital exhibit – that is the way of the future.”