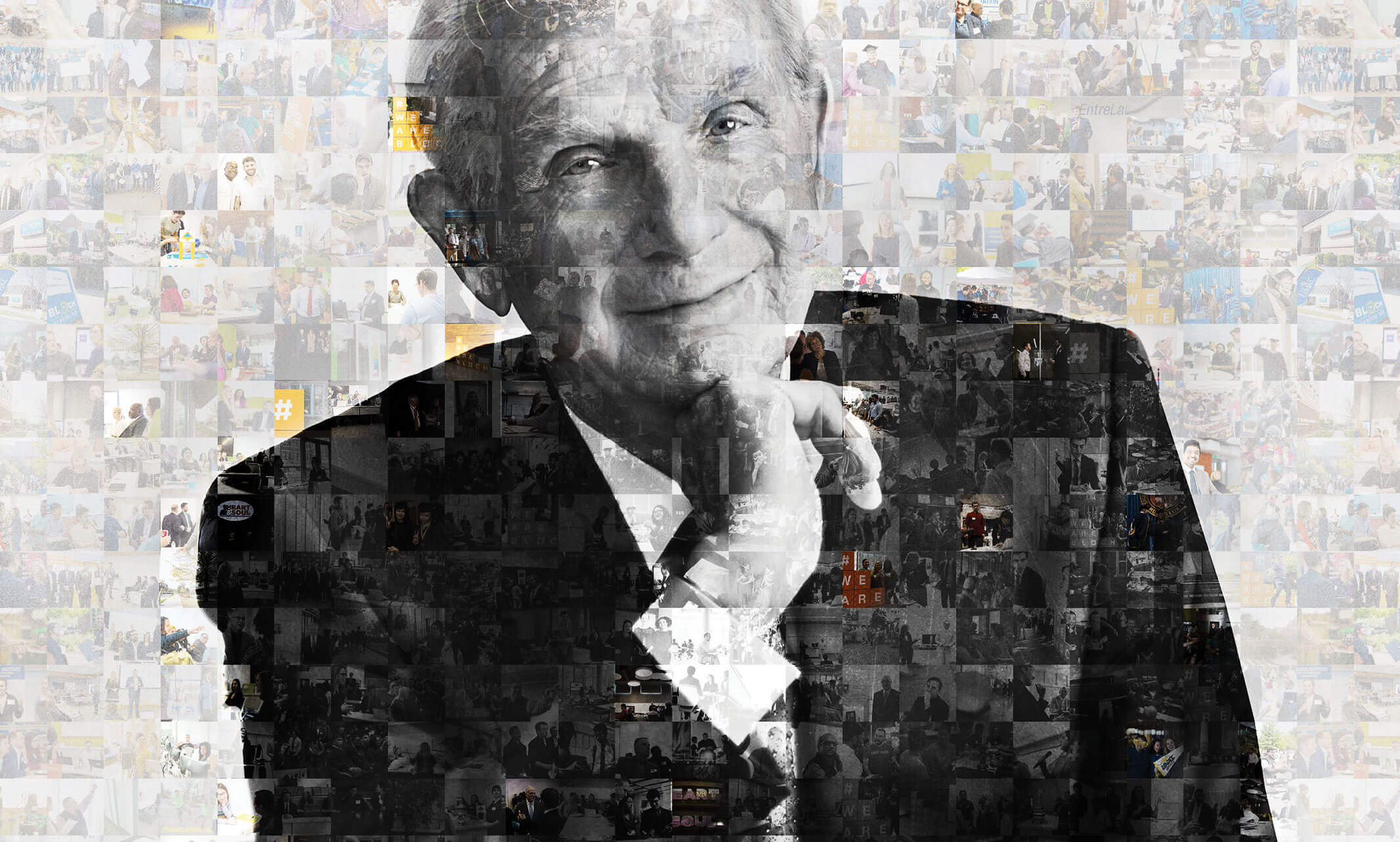

Henry W. Bloch knew how to leave an impression.

Brian Klaas, Ph.D., Bloch School dean, remembers vividly how gracious and kind Mr. Bloch was, even when he was emphatically making a point.

“Henry and I were having a wonderful conversation about H&R Block, Kansas City and the Bloch School,” Klaas recalled. “Mr. Bloch paused, leaned in and said, ‘We need to help the Bloch School achieve excellence, and we need to do it quickly. We need to do it for Kansas City because this city needs a great business school. Are you going to be a part of this?’”

The quest for excellence long guided Henry. He was an investor and he expected a return of excellence. The Bloch School was his investment, forged as a freshman at UMKC, then called the University of Kansas City.

Through good times and bad, achievements and struggles, Henry was all-in with Kansas City’s business school. Up to the end of his life, Henry was working on making the Bloch School excellent.

That was his mission.

That is his legacy.

“When I look around Kansas City and look at all the places where Henry has made his mark, I think one of the most incredible places is the Bloch School,” said Jeff Jones, president and CEO of H&R Block. “When I think about legacy and future, the idea that his name will continue to spawn the next generation of entrepreneurs that will go on to have success in Kansas City and beyond is one of the most incredible representations of what legacy can be about.”

How this legacy began and how this legacy lives on in others is a testament to his values that will endure long into the future.

A kid from down the block

When Henry died on April 23, 2019, at the age of 96, he left behind a well-documented life. He was many things: entrepreneur, executive, philanthropist, husband, father, avid fan of the Royals and Chiefs.

He also was a study of contrasts. He was someone who repeatedly said he wasn’t very intelligent but demonstrated he was extraordinarily intelligent, shrewd and insightful. He was a humble young man who went on to become a war hero. He was someone who claimed his success was simply luck but also worked very hard, developed sound business strategies and executed them in a masterful way.

And he was someone educated at the top universities in the country who purposely invested his time and resources over the course of decades to the business school of the local university he only attended for one year.

“He was a pretty interesting individual. All these things were opposites but he bridged them together,” said UMKC Chancellor C. Mauli Agrawal, Ph.D. “That was perhaps the source of what distinguished and differentiated him as a person and made him stand out.”

Henry grew up at 58th and Wornall and went to Southwest High School. When he came to what was then the University of Kansas City, both Bloch and the university were young. Henry graduated early from high school and was unsure of his direction and his abilities.

“This was his first real effort at becoming a grownup,” said John Herron, Ph.D., interim dean of the UMKC College of Arts and Sciences.

At UMKC, Henry discovered a passion for mathematics and the first signs of it being a possible career. While his academic skills grew at the University of Michigan and his short time at Harvard Business School, it started here.

UMKC, starting a few years before Henry’s arrival in 1933, was part of Kansas City transitioning from its cowtown image into what would become a booming metropolitan area. While the university offered business classes, it would be quite some time before a bona fide business school would spring up.

Herron recalled asking Henry about moving away from Kansas City or giving to other places outside the region.

“Henry was incredulous at the question. ‘Why would I have done that? Kansas City gave me everything,’” Herron said.

Herron thinks that comes from Henry’s perception that he and H&R Block really couldn’t have made it anywhere else. Unique conditions allowed the business to grow: postWorld War II economic booms, the Internal Revenue Service halting its free tax preparation service and a growing metropolitan area in Kansas City.

But Henry was cognizant of the cultural sensitivities of Kansas City. After all, Henry and Richard Bloch were two Jewish brothers who walked down Troost Avenue and Main Street, talking with African-American businesses about helping with their bookkeeping needs.

Henry’s service during World War II amplified that contrast of modesty and doubt and achieving success through hard work. Herron and Mary Ann Wynkoop, a retired UMKC professor and former director of the American Studies Program, co-wrote “Navigating a Life: Henry in World War II,” which chronicles Henry’s days in the U.S. Army Air Corps.

For all the adventures and accomplishments, this stood out to the two authors: Henry was someone who noted the taxing nature of navigator training and wondered if he could complete it, but ended up completing 32 missions without a single injury to himself or his crew. He was a war hero but he would never admit it.

Henry, in conversations with Herron for the book, would say his successes, like so many things in his life, were the product of luck. But other values were taking root, like hard work, discipline and, because of the war, losing his fear of failure. And perhaps most important, being faithful to where you came from.

Herron said UKC was a critical time in Henry’s life, one that he looked back on with fondness.

“He was trying to figure out what are the proper boundaries of adulthood, and it all came together for him here,” Herron said. “He felt a great connection to the place.”

And that connection would be the foundation to build upon the small business school at UMKC.

Going all in

While Henry and Richard were building H&R Block, the university was struggling to get its business school going.

According to Chris Wolff, who researches UMKC history, the school of business started on a shoestring budget and a desire for business classes.

The school didn’t have its own facility until the university bought the Shields Mansion. But the school quickly grew and was soon competing with its neighbor, Rockhurst University, for top business students.

In 1983, Dean Eleanor Schwartz, who later became UMKC chancellor, convened an advisory committee of local CEOs to help the school meet the needs of area employers and achieve accreditation from the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business, the premer accreditation body for business schools.

The mansion was in dire need of renovations. With project plans totaling $7.5 million, the University of Missouri System allocated $6 million toward the renovation. The rest was to be left to private donations.

By this point, the Bloch family had already funded the Leon Bloch Law Library for the School of Law in 1978. Seeing a way to help, Henry gave $1 million toward the school.

It led to an intriguing offer.

“(Former UMKC Chancellor) George Russell and (former UMKC Trustee) Ed Smith cooked up the idea of naming the business school after me,” Henry said in spring 2002. “The first I knew about it was at a board meeting. I was very flattered.”

“Henry saw his involvement with UMKC as a way to combine his love for Kansas City and his passion for business,” said David Miles, president of the Marion and Henry Bloch Family Foundation.

"With his namesake on the building, Henry saw an opportunity. He recognized a need within the region for a high quality and respected school of management that would create the next generation of entrepreneurs and business leaders, which he saw as an exciting and worthwhile goal,” Miles said.

Those who knew Henry know that once he was committed, he was committed for life and in all things.

“It struck me that with Henry, there wasn’t a half in. You were all-in or you weren’t,” Klaas said. “Once he made that commitment, he was not going to waver. He was going to be focused on the mission.”

Thanks to Henry’s investment, the Bloch Executive Hall of Entrepreneurship and Innovation opened in 2013.

“A tapestry that works”

When Henry was a student, the term “entrepreneurship education” did not exist. There was no formal educational component to learn the ins and outs of entrepreneurship. The only instructors were the hard knocks of life and business.

When the opportunity came to shape the future of the Bloch School, Henry wanted to make sure teaching the principles of entrepreneurship was top of mind.

Anne St. Peter, who founded Global Prairie, a global marketing consultancy, said that Henry was fond of telling entrepreneurs not to fear making mistakes, as he and his brother made many of them.

“The goal, Henry said, was to learn from these mistakes and to develop resilience along the way,” she said. “Henry told me his support of the Bloch School was to help entrepreneurs learn from the mistakes he and other business leaders made and, hopefully, allow Bloch students to learn valuable business and life lessons quickly.”

Henry’s lessons on entrepreneurship inspired many like St. Peter. Both she and Henry were past chairs of the board of the Kansas City Chamber of Commerce. At a luncheon, Henry

told St. Peter to relish the opportunity to serve the business community of Kansas City.

“At the time, I was the youngest leader to serve as Chamber chair, and Henry knew I had two small children,” St. Peter said. “Henry told me to share what I was learning at work and at the Chamber with our children, as he had done with his children while they were growing up. Henry encouraged me to bring our children along for the ride and make them feel a part of my entrepreneurial journey.”

St. Peter admired Henry and his leadership greatly. He served as inspiration for her to certify Global Prairie as a Benefit Corporation, or B Corp. For Henry, community engagement and employee happiness mattered as much as shareholder value.

Another component of entrepreneur education was having a strong physical presence in the community in which you serve. For the Bloch School, that meant state-of-the-art academic and research facilities. In 2011, the school was ready for a substantial upgrade. Just as in 1983, Henry chose to invest, putting $32 million toward a new building.

“I choose to make this significant gift because I felt now was the right time,” he said at a celebratory event on Sept. 15, 2011. “The new mission and vision of the school both respect and directly tie into the legacy of Kansas City and align with what this community wants and needs from its business school.”

Leo Morton, who was UMKC chancellor at the time, said Henry was the right person to do this because he understood that to build a reputation of excellence, you have to have the infrastructure to back it up.

“One advantage UMKC has is its location. If you’re a student who has lots of options and are world class, you can go any place you want to go,” Morton said. “To recruit and retain these students, you need to have faculty that they’re attracted to, and you have to have facilities that match all of that. It’s a consistent picture, a tapestry that works.”

A first-generation investor

Within the timeline of UMKC benefactors, Henry falls in line with the likes of Stanley Durwood, Miller Nichols and Helen Spencer, who built upon the foundation of UMKC. Wolff said Henry’s contribution helped steer UMKC toward the modern era of education.

“Mr. Bloch grew up in an age where it was possible to invent an industry from scratch. He saw that the future of business lay in innovations such as the ones that were created at H&R Block,” Wolff said. “Now that we live in the digital age where once again businesses and entire industries can be invented out of whole cloth, the Bloch School is on firm footing to train the next generation of business leaders and entrepreneurs in this new world.”

Henry was a philanthropist who gave generously. And yet, he was an investor at heart. Morton, who knew Henry for many years before he became UMKC chancellor in 2007, said Henry invested with a sense of purpose, and he wanted a return. When it came to UMKC, he was a first-generation investor.

When investors like Henry invest, “they don’t just put it in and leave you, they put in and hold you accountable,” Morton said. “The investor says, ‘I had an objective when I invested in you and that objective is important to me and I put in enough to show that I’m serious about that investment. And I’m going to hold you accountable.’”

That objective, for the Bloch School, was for it to be excellent. And that’s something Klaas said continues today through the Bloch Family Foundation.

“What the Bloch Family Foundation wants is what Henry wanted: It’s for the Bloch School to help this region thrive. They want us to support the region by pursuing excellence in everything we do and by offering outstanding experiences for students from all backgrounds and at all stages of their careers,” he said.

“Never despise small beginnings”

Henry Wash never had any desire to go into business.

One of the first members of the Henry W. Bloch Scholars program in 2001, he didn’t know much about the scholarship or the man for whom it was named.

He went to the scholarship reception fully intending to drop out of the program.

Then he met Henry Bloch.

“I arrived 30 minutes early and my plan was to get out of it. Mr. Bloch was there when I walked in, just standing,” Wash recalled.

Henry Bloch was early as well. After pleasantries and realizing they had the same first name and middle initial, Wash shared his hesitations.

“I wanted to let Henry know that I’m wanting to get out of this,” Wash continued. “I just wanted to help people. So, I was telling this long story. He was looking at me and when I was done, he said ‘I want to help you. I want to mentor you and help you along.’”

“I was thinking to myself, nah, he wouldn’t want to do that, not for a guy like me,” Wash continued. “And he said, ‘Oh, I really do.’”

That started a long friendship and mentorship that lasted many years. The Henrys spent many a lunch talking about business and life. Henry Bloch visited the Wash family often and sat on the front row during Wash’s wedding.

“I was taught to never despise small beginnings,” Wash said.

Henry knew that investment was more than just funding. It’s about people: where they came from, what they’re about.

“Every time there were students, he wanted to mingle and speak,” Agrawal said. “He was not supporting the Bloch School for the publicity. It’s because he really cared about the students, and that stood out clearly.”

The Henry W. Bloch Scholars program at UMKC, of which Wash did stay in and graduated from in 2003, is now a 20-year commitment to provide those highly qualified students a path toward a degree. It helped students like Marla Howard, who completed her degree in Fall 2005.

She said in 2006 that, “my family hasn’t had a lot of opportunities and isn’t as financially stable as others. So, I was determined to take advantage of any opportunities that crossed my path.”

Wash and Howard are just two of the many students who have been impacted by Henry and the Bloch family’s investments. With the Henry W. Bloch Scholars and the Marion H. Bloch Scholars programs, both high potential and excelling students living in underserved communities attend UMKC on scholarship.

Many students are currently being supported by the Bloch Launchpad program, which combines academic rigor with professional development training.

It’s an investment for success with the goal of – taken from Tom Bloch’s biography of his father – many happy returns.

We are Bloch

To be sure, there is only one Henry Bloch. He is irreplaceable. But his values and the relationships he’s built with UMKC and the Bloch School are the road map for others to make an impact as he did.

“Henry was an amazing example for how supporting a school can make an important difference in the lives of so many,” Klaas said. “We are fortunate to have a number of supporters who were inspired by Henry’s work with our school. And we look forward to building upon Henry’s legacy by engaging with other alumni and supporters who are inspired by our mission.”

The impact is fundamentally relational: Bloch alumni who mentor students, build a company or entrepreneurial venture and fulfill their own debt to Kansas City and beyond.

They carry on Henry’s legacy.

Although Henry came from another generation, what is timeless and relevant are his values: working hard, persevering, learning from customers, serving, giving back generously and never forgetting where you came from.

Agrawal sees Henry’s life and example as imperative to building on that legacy of excellence.

“We are good, but we need to be excellent,” Agrawal said. “So that a student in 2042, when they come to the school, somebody will be asking them where they want to apply and they’ll say, ‘I want to apply to the one of the best. I’m applying to Bloch.’”

This story originally appeared in the 2020 issue of Bloch, the magazine for the Henry W. Bloch School of Management.