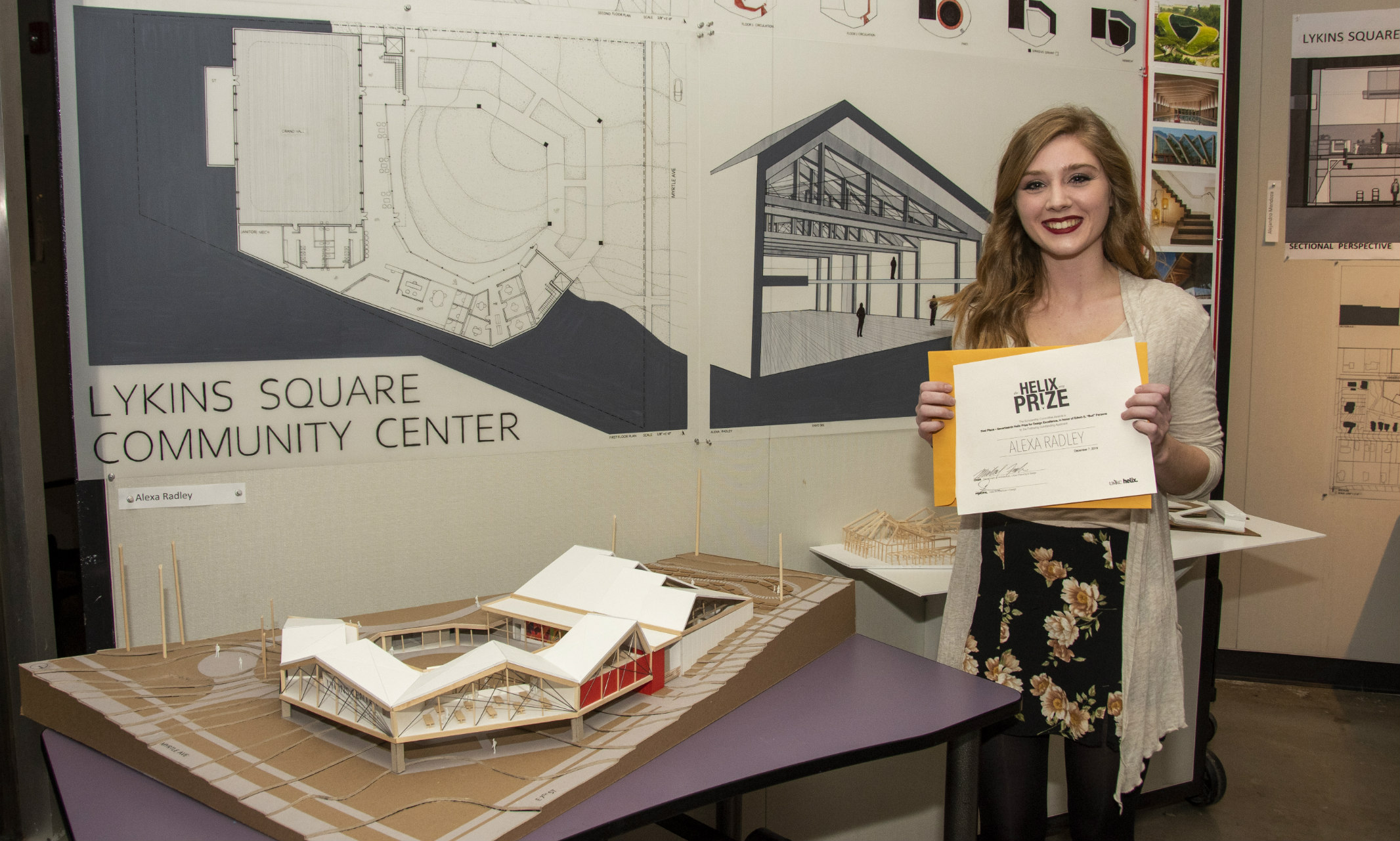

Alexa Radley carefully lifts the roof of the model of her prize-winning design in the unusually quiet studio space of Katz Hall. She points to colorful, geometric art that spans a large section of the wall.

"I suggested having a local artist create a mural here,” she says of her design for a community center in the Lykins neighborhood in Northeast Kansas City. “I think that would really help make it their own.”

Museum board, basswood, heavy-gauge wire and tiny plastic people are the tools that the students of the Architecture, Urban Planning and Development program use to translate the needs of their clients into physical solutions at the annual Helix Prize competition for the second-year students.

For this year’s class, these models — diminutive in scale — represent the strengthening of a neighborhood in the development of a new Lykins Square Community Center.

“While this is not a real project, we did meet with representatives of the neighborhood association, and they gave us feedback on what the neighborhood would want,” says John Eck, associate teaching professor. “The neighborhood owns the site and sees it as a possible ‘real’ location.”

Eck says there were a couple of interesting challenges with this project, especially as the residents included gym space as part of their wish list.

“One of the biggest challenges was the insertion of a fairly bulky building into a very modestly-scaled residential neighborhood. No one wants a giant new building looming over their home, but at the same time the design needed to accommodate the program and address the large scale of the park.”

In addition, the slope of the site is significant.

“There’s a drop of about twenty feet from the back of the site to the front sidewalk,” Eck says. “Finding a way to “step” the program down, both indoors and outdoors, while maintaining accessibility for all is no small feat.“

Radley came to the AUPD program after a year in community college. With equal strengths in art, design and math, she thought architecture might be a good fit.

“I interned with A3G in Liberty, Missouri,” she says. “It’s a small firm of women architects. It was a great way to see if I would enjoy the field.”

Her experience assured her that architecture was her path. She was accepted into the program and will continue to Kansas State University as part of a partnership between the two universities.

"You get really close to the people in the program."

For the Helix Prize, students had seven weeks to outline their objectives and approaches, complete structural drawings and build their models.

“It’s a big project,” Radley says. “There are a lot of small components. Dealing with the topography of the sloped site was a real challenge.”

When she began her design, she envisioned the roof as a ramp, but as the design evolved, she incorporated angular silhouettes to mimic the roofs of the neighborhood.

“That’s when I really started to love my project,” she says.

Radley’s design is nestled into the landscape, creating the feeling that the neighborhood both surrounds and protects it. Her building has more movement than some of her classmates, whose designs relied largely on right angles. She included orange panels on the exterior as a warm and inviting accent. But one of her favorite components was the mural.

“The community representatives really love it,” she says.

This year’s jurors included Gail Lozoff, neighborhood representative; Mike Frisch, department chair, AUPD; Katie Kingery-Page, landscape architect and Kansas State University representative; and Anthony Luca. And despite what might look like an intimidating and very personal process to have professionals critique their student projects, Radley did not find the process daunting.

“Most of the jurors have been through the process, so they understand what it feels like. Their feedback is very constructive and they focus on strengths as well.”

Radley and the runner-up, Anna Greene, will both receive scholarships to Kansas State next year. Radley is looking forward to their transition.

"You get really close to the people in the program,” she says. “We’re all in the same classes and studio together, which is more intimate. Most of us are going on to K-State next year.”

While she loves the field and the program, she cautions that it’s not for everyone.

“The program itself is challenging and not everyone who has an interest decides to tough it out,” Radley says, as she carefully replaces the roof of her model. “If you’re not 100% committed, you’re not going to make it. There were 36 first-years in my class. We’re down to eight.”

Eck is not surprised that Radley is one of the remaining eight.

“Alexa’s design process and work ethic is actually what was most striking to me. She has a remarkable ability to put her head down, focus, move forward, and get it done. The end product is important, of course, but learning how to get there is even more important. Design studios are about teaching design process; the project is just a vehicle to do that.”