Every year, hundreds of students, faculty, staff and visitors pass the vibrant murals of Luis Quintanilla, the Spanish expatriate who spent part of his exile from Spain creating the work for the University of Kansas City (UKC).

Julián Zugazagoitia, director of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, has a compelling connection to the murals — one he only discovered when he saw them firsthand.

Zugazagoitia had lived in Kansas City for five years before he climbed the marble steps to the second floor of Haag Hall to investigate the legacy between his family and Kansas City. Quintanilla and Zugazagoitia’s grandfather, also named Julián Zugazagoitia, were friends and soldiers in the Spanish Civil War, fighting the fascist regime of General Francisco Franco.

Quintanilla and Zugazagoitia had been in prison together in Spain in 1934, where the artist sketched his friend and compatriot.

“I’d seen an exhibit in New York that included the drawing of my grandfather,” says Zugazagoitia. “Not long after, Quintanilla’s grandson sent me an email to tell me about the murals. It was in the back of my mind, but I had not made it over to see.”

A Presidential Request

Quintanilla came to UKC in 1940 to serve as its first artist-in-residence at the invitation of UKC President Clarence Decker. At 34 years old, Decker was the youngest-serving president of the country’s youngest university. He suggested Quintanilla paint a mural in Haag Hall using the theme, “Don Quixote in the Modern World.”

It was a bold move for the college president, considering Quintanilla’s political past.

“The national mood in 1938 was certainly one of unease,” says John Herron, associate dean of the College of Arts and Sciences and professor of history. “The effects of the Great Depression were still apparent, and the growing militarism and unrest in Europe did little to calm fears. Americans, for the most part, wanted nothing to do with a second world conflict and were eager to stay out of European politics.”

Decker, a vocal proponent of the arts and culture, used his role at the university to cultivate relationships with many politically informed artists.

“He offered visiting appointments to a number of artists, poets and writers, and worked actively to make Kansas City a kind of avant-garde center in the American Midwest,” Herron says. “Decker understood the hostility many artists and scholars, especially Jews, faced abroad. He remained a proponent of bringing these artists to Kansas City whenever possible.”

Quintanilla's Vision

At the time of Decker’s invitation, Quintanilla was living in New York as part of the Rockefeller Foundation’s Committee for Displaced Scholars and Artists program that brought oppressed and imprisoned artists from Europe to the United States. His art had recently been shown at the 1938 World’s Fair in New York.

Quintanilla envisioned four panels using Don Quixote’s story as an allegory of the horrors and oppression of fascism in Europe. The artist used members of the university faculty and staff as models. His own family appears in one panel.

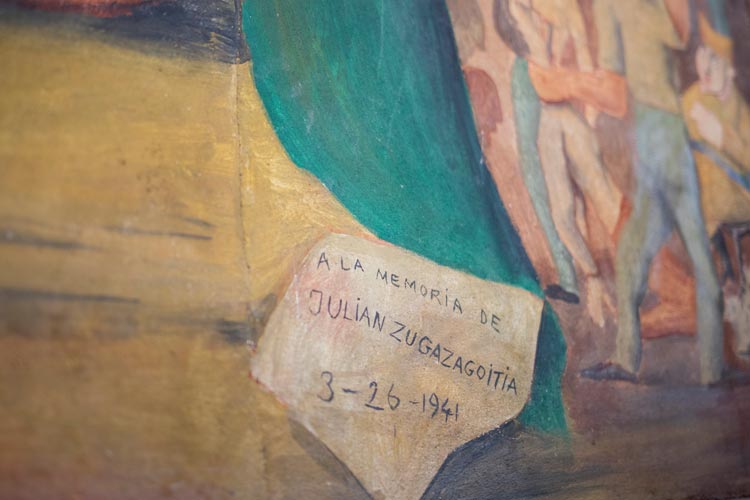

Zugazagoitia, who was aware that Quintanilla used family and friends as models in his work, expected to find his grandfather’s face looking back at him from the walls. This was not the case, but what he discovered was even more powerful.

“When I saw he had dedicated the mural to my grandfather I was stunned. To see his name — my name — in the corner … It took a while for me to process, but it fulfilled a notion of destiny for me. Finding his name confirmed that Kansas City is where I should be.”

Modern-day Revelations

Beyond his personal connection, Zugazagoitia was reminded how significant it is to be an immigrant. He sees the murals as a reminder of what it takes to make your way in a foreign place.

“It underscored for me how important it is to reinvent yourself in a new country. It seems the perfect time to be talking about this,” he says.

Zugazagoitia emphasizes how important it is to preserve these murals. Besides recognizing the work for its artistic and historical merit — it is one of only two Quintanilla murals that were not destroyed during the Spanish Civil War — he believes living with art changes those who are exposed to it.

“Our experience is better because it exists. We are privileged to live in an environment that nourishes us, even if we don’t notice,” he says. “It makes these stories meaningful and present in our lives.”

This article originally appeared in the 2018 issue of Perspectives, the UMKC alumni magazine.